Worlds Apart

The township of Auchindrain is a hidden gem tucked away in the hills that separate it from Loch Fyne, perhaps offering it some needed protection against the winds that buffet the shores. The modern day A83 runs right past Auchindrain and people can easily miss the old red roofs that cover the buildings as they drive past the last remaining township in Scotland.

Nowadays we can enjoy the comforts of modern vehicles and a decent road system to take us anywhere we want to go. Back to Glasgow, down to Campbeltown, or perhaps to the ferry that runs between Kennecraig and the island of Islay. With all this luxury it is hard to picture what life would have been like for the people of Auchindrain. They were mostly self-sufficient in growing their own food, made their own clothes from start to finish, and traded for other items with passing Gypsy-Traveller “Tinkers” as they made their way through Scotland selling goods and providing much-needed seasonal labour. On rare occasions some of the people of Auchindrain would have bought items from shops in Inveraray, but the six miles between Auchindrain and Inveraray would have taken a long time to cover on foot, and even on horseback. Life for the rural working class in 19th century Scotland was not easy.

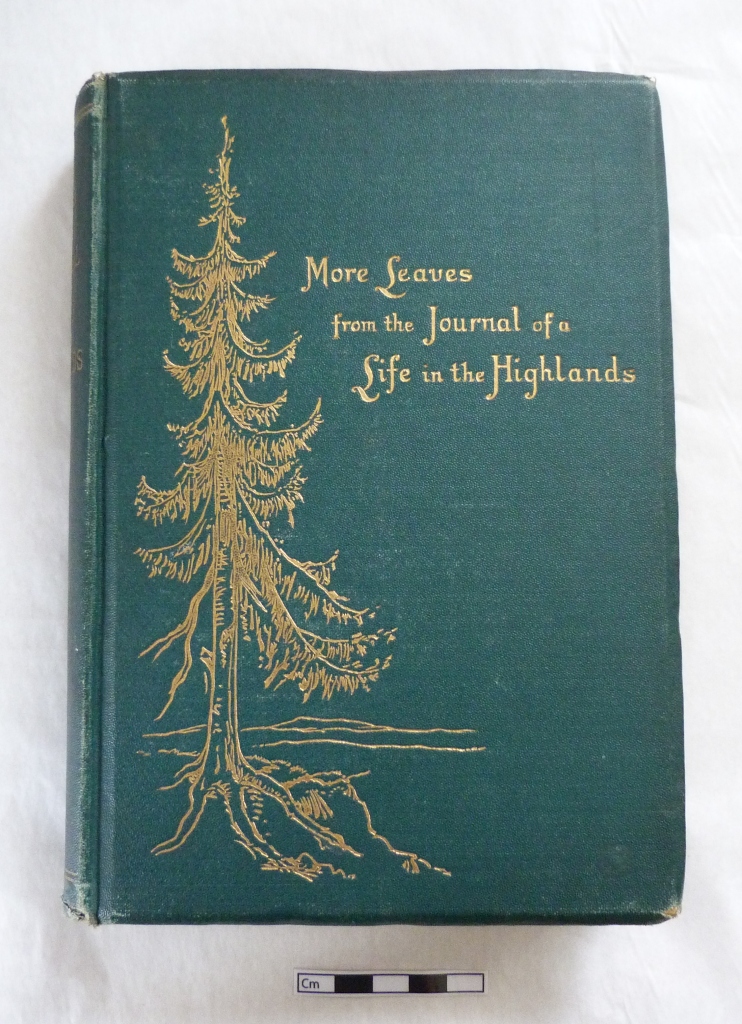

All this makes me wonder what Queen Victoria was thinking during her visit to the area on 25th September 1875. She had been staying with her daughter Louise, then Marchioness of Lorne, at the Castle in Inveraray. That Saturday, “a pouring wet morning”, she had breakfast with her daughters and subsequently spent the afternoon driving along the road to Lochgilphead. Later, they accompanied her and George Campbell, Duke of Argyll, on an evening drive-out to see the “primitive villages” of Achindrain and Achnagoul. In her journal, the Queen talks about how a “curious old practice, now fallen into disuse, is continued” in these places, and refers to a letter sent to her by the Duke in which he talks about Auchindrain and Achnagoul as townships in which people hold joint tenancies and work the land communally, casting lots yearly to redistribute the land.

The Queen’s journal has been a valuable source of information for Auchindrain, even if what was mentioned was just small. It helps us to establish a timeline and provides some background history. These journals however, as with most travel journals, only give us one side of the story. The perspective offered by Queen Victoria is in essence that of an anthropologist creating a harmful “us” versus “them” narrative. The wealth of the south compared to the “semi-barbarous system” of land-holding and use that, according to the Duke, was until quite recently still being used in the townships of Auchindrain and Achnagoul. If only we could hear the story from the perspective of the people of Auchindrain, because at the end of the day the people that lived here are more than just scribbles in a journal, more than just numbers and names on a census. They were hardworking people whose stories deserve and ought to be told in a way that honours their history.

The modern day museum that is Auchindrain Township is preserving the stories of the people that lived here and has figured out a thoughtful way to share this information with its visitors. Alongside information about the township itself, short stories about the occupants of the houses are included in the tours as visitors walk around the township. Aided by eyewitness testimonies and oral histories, the museum captures the essence of what makes this place so unique: the lives and work of its inhabitants.

Image: Cover of More Leaves from the Journal of a Life in Highlands.