Emilie von Berlepsch: a German traveller in Argyll in 1800

Useful historical Information can come from unexpected sources! In 1800, the German writer Emilie von Berlepsch (1755-1830) visited the Highlands.

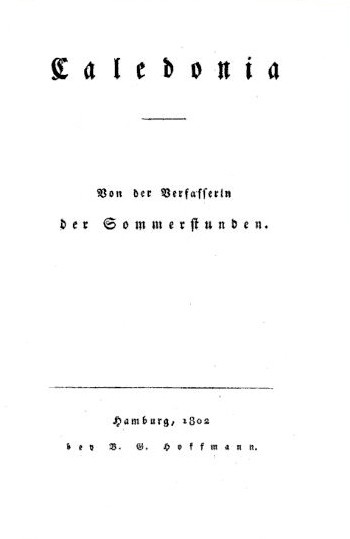

Her account was published as Caledonia, the first German-language travelogue of Scotland. A popular success at the time, this has largely been forgotten and does not seem to have been translated into English. It was recently rediscovered by one of our 2017 International Interns, Daniel Baumbach, whilst seeking an equivalent in German for the word “township”.

Emilie von Berlepsch was an educated woman who moved in the circle of some of the great German poets of her time including Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. She was an admirer and translator of Burns, and of Macpherson's Ossian. Interested in poetry, castles and the beauty of nature, she was also concerned with social justice and women’s rights. Caledonia provides interesting insights into rural life in Argyll around 1800, at a time when industrialisation and agricultural improvement were causing the disappearance of the traditional way of life of the joint tenancy townships.

Von Berlepsch spent time in Argyll including a visit to Inveraray. I leave Inveraray very unwillingly. Seldom have I liked a place so much, it is very rare to see such a connection of nature and art, she wrote about the castle. She was interested in the common people, and offers a snapshot of their life in a way overlooked by most contemporary writers.

At that time, joint tenancy townships were being improved into crofting townships. She thought this highly unfair, because leases only lasted a few years and people were often then evicted so the land and everything on it could be sold. Discussing the “vicious financial operations” of landowners, she observed that such a practise of its nature prevents the common people from increasing their wealth, and kills industriousness. Nobody dares to do anything because they cannot take the risk, for themselves and their children, of being expelled from their hearth and field.

She did, however, approve of the Duke of Argyll’s efforts to improve the lives of the people on his land by giving them longer leases and financial support for building houses. She recognised problems with the move from cattle to sheep then being promoted by the improvers: like in most German provinces, the common man cannot survive here without cattle. She also wrote about the Duke’s unsuccessful efforts to establish manufacturing industries, with the reluctance of people to follow his lead being something she did not understand:

There seems to be something in the mentality of the Highlanders that resists a steady, persistent diligence. They are too much used to fishing and cattle breeding to be easily persuaded of the necessity of manufacturing industry.

She does not mention Auchindrain by name, but there is much in her writing which chimes with what we know from other sources. The Duke about whom she wrote was John, 5th Duke of Argyll. It was he who, in 1789, commissioned the land surveyor George Langlands to draw up schemes for the improvement of his “farms”, but who then declined to implement Langlands’ proposal to divide Auchindrain into 24 crofts. We know well of the Duke’s failed investment in a weaving mill at Claonairigh, two townships north of Auchindrain, which opened in 1776 and closed in 1806 in part because he could not get the women of the townships to spin for him – at Auchindrain, all except one refused because they were too busy. We also know from the Old Statistical Account about the misery caused by exploitative landlords and short leases, and the problems caused by the early attempts to replace cattle-breeding with sheep kept for wool.

It is fascinating to read the thoughts on such matters of an educated, female, German traveller, who would have been a complete outsider in the Inveraray of 1800 but whose words ring true today.