Women’s Wartime Contributions on Scotland’s Railways

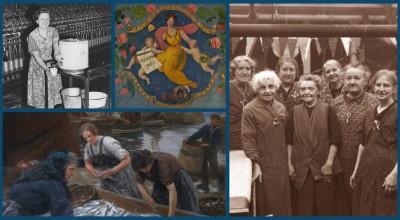

To commemorate the centenary of the end of the First World War in 2018 our temporary exhibition “From Scotland to the Somme” looked at the many ways the war affected Scotland and its railways. To celebrate International Women’s Day on March 8th, here is what we discovered about the challenges of women during wartime.

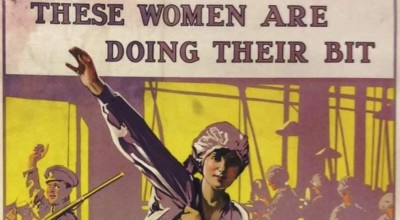

Prior to the outbreak of the war, women made up almost a third of the workforce in the UK. Many worked in domestic service, which was traditionally seen as appropriate for the fairer sex. This changed after thousands of men left to fight, leaving many jobs vacant. These jobs were then taken on by women. For many the idea of women replacing men in especially railway jobs was a hard pill to swallow, and was met with resistance.

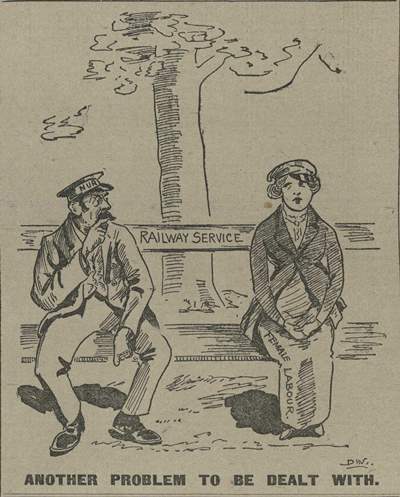

To ease rising tensions, an agreement was made in April 1915 between the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR) and the recently established Railway Executive Committee, regarding the employment of women. The following terms were agreed to:

To ease rising tensions, an agreement was made in April 1915 between the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR) and the recently established Railway Executive Committee, regarding the employment of women. The following terms were agreed to:

- Women’s war work would not be regarded as setting a precedent for their employment in peacetime;

- Soldiers returning from service would be guaranteed reinstatement;

- Women would receive no less than the minimum male rate.

The third point was to ensure the protection of the rates of men upon their return, not to improve the rates of women. Women earned less than men for doing the same work, and at worst would only make 1/20th of a man’s salary.

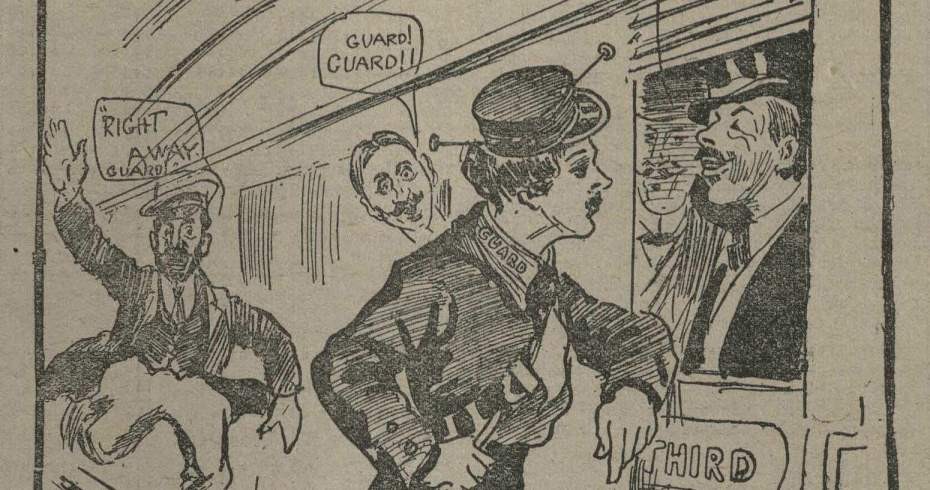

Despite the initial resistance Scottish women were eventually hired for a vast array of jobs, such as clerks; carriage cleaners; signalwomen; guards; ticket collectors; labourers; porters; and wagon painters. The one job women were never allowed to do was actually drive a locomotive. None of the work was not easy and at times could be dangerous. A report on female NUR members being killed on duty mentions at least five incidents in Scotland:

- Amelia Crewel, Porter for Caledonian Railway – struck by train at Hamilton on July 14th, 1916

- Mrs Nelson and Mrs Monroe, Carriage cleaners for North British Railway – knocked down by train at Glasgow Queen Street on July 27th, 1916

- Mrs McCormack, Porter for Caledonian Railway – hit by express train at Midcalder on August 23rd, 1918

- Margaret Barclay, Distiller for North British Railway – run over by an engine at Cameron Bridge on September 19th, 1918

One of the most significant changes came about as a result of dangerous working conditions – the changes to the uniforms. Female guards, having to jump on board a moving train after giving the all-clear, found their floor-length skirts not only impractical but also a safety hazard. This led to a “compromise” of knee-length skirts with knickers tucked into the boots in an attempt to preserve the ladies’ modesty. This soon led to some women adopting men’s clothing, which was considered rather scandalous at the time. Female carriage cleaners, for example, created a type of makeshift trousers although women working in more public-facing roles did not change their attires.

By the end of the war women had more than proved their capability in railway work. However, attitudes towards women in “men’s jobs” had not changed. The numbers of women workers diminished significantly, almost as fast as they had grown. As an example of this, there were 35,000 women working in male wages grades in November 1918 – within five years, this number had dropped to less than 200. Though some gave up their positions willingly, many women were dismissed from their duties without a proper explanation. Women would wait for another two decades to take on the men’s work again during the Second World War, after which they were able to hold on to their jobs in somewhat greater numbers – but were still not allowed to drive the trains.

Museum opens again for the season on March 23rd and the temporary exhibition will remain open until the 28th of June to mark the centenary of the Treaty of Versailles.

Images courtesy of the Modern Records Centre at the University of Warwick.