The Old ‘New House’

Beatrice Law, a History of Art undergraduate at St John’s College, Oxford, spent the summer of 2018 at Auchindrain. She was researching the plenishings and interior decoration of ACHDN.Z, The New House, in preparation for its restoration when, in the future, the building can be released from its current role as the museum’s offices.

‘Young Eddie’ MacCallum, born in 1946, is the son of Eddie MacCallum, the last tenant of Auchindrain, and his wife Peggy Cuthbertson. As a child Young Eddie liked photography, using both a Box Brownie and an SLR bought for him abroad. In 2012, he donated to the museum his photographs of Auchindrain and a quantity of old family papers.

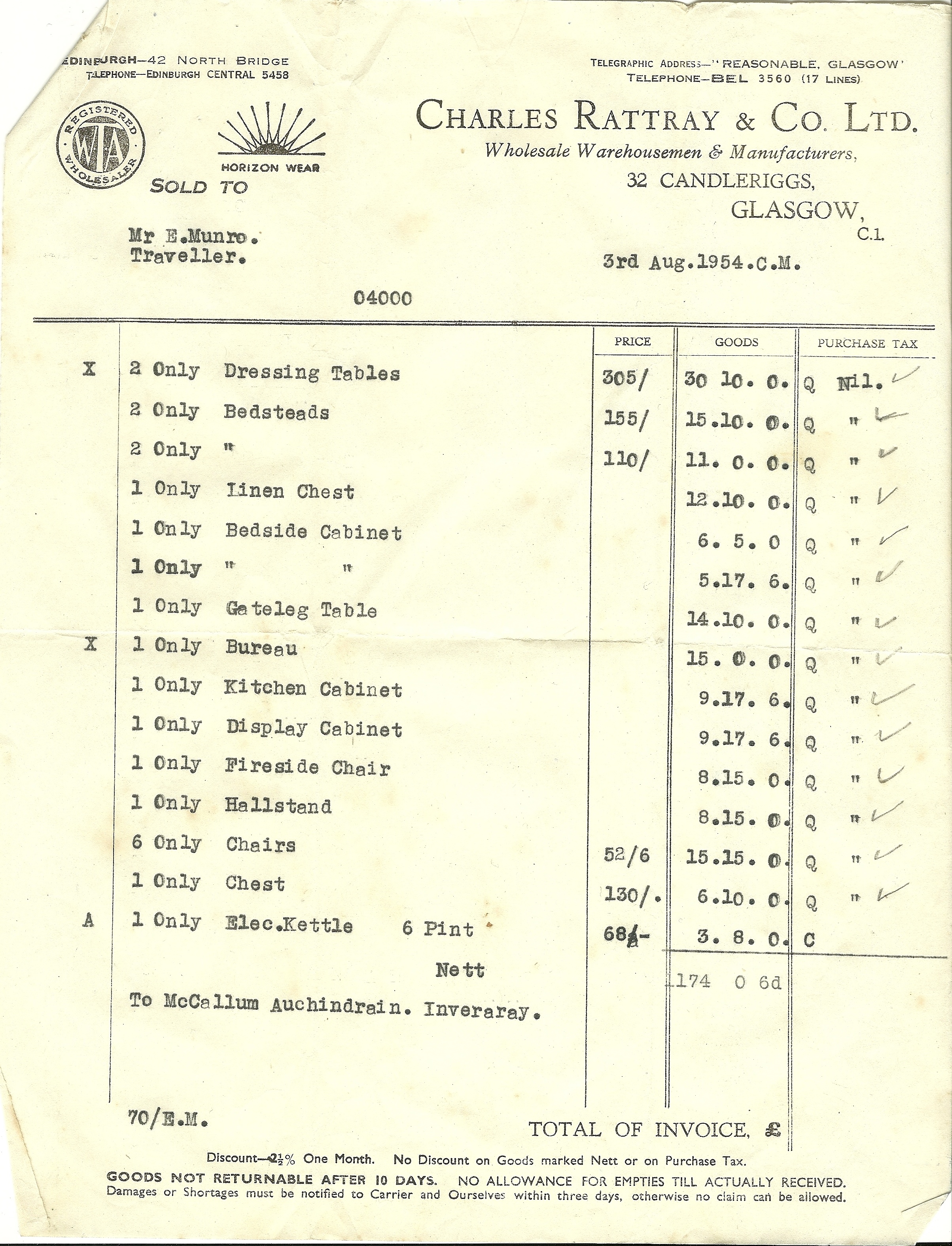

In researching the interior décor of The New House at Auchindrain, I have taken advantage of a range of primary sources from the years following its construction in 1954. These include photographs taken by ‘Young Eddie’ MacCallum, Young Eddie’s memories, and the itemised receipt for the furniture purchased to outfit the house when new.

In 1953, Argyllshire County Council had informed the Argyll Estate that the MacCallum’s previous home (‘Eddie’s House’) did not meet new minimum standards for a house to be let to a tenant farmer. Rather than upgrade the existing building, the Estate replaced it with a brand-new, pre-fabricated timber house produced in Kent by WH Colt, Son & Co. Ltd. Young Eddie and the rest of the MacCallum family moved to The New House in the spring of 1954 and lived there for nine years, before they gave up the tenancy of Auchindrain and the house passed it on to Willie Weir and his wife Ann Luke. Young Eddie, like The New House, has somewhat outgrown his nickname, but he is still more than capable of shedding light on areas other sources do not cover: the detail in his memories reduces the need for much of the guesswork that would otherwise be required to suggest what the interior of the house was like when it really was new.

Eddie began our conversation by insisting that he didn’t think he would be of much use to my project, but that was far from the case. Walking around the house with him in its current form as the museum’s offices was a wonderful opportunity to get into the kinds of specifics that no one thought to record at the time. I had prepared six pages of questions about the décor in advance of our chat, and Eddie managed to answer almost all of them. Using the documentary sources as prompts where needed, we managed to piece together much of how the interior of the house was arranged in the fifties. No longer was the 1Only Kitchen Cabinet listed on the 1954 receipt for £9 17s 6d simply a typewritten abstraction, but a glass and plywood display case with fold-out doors at the top and bottom in which Eddie’s mother had kept her best china (although he did not remember what the china looked like due to the infrequency of its use!).

Such vivid specifics highlight how every source, even one as detailed as the receipt, can only give a partial view of the past. Most records fail to capture the vital snapshots of real life that sneak in around the edges of the facts. For example, Eddie told us that the MacCallums installed their own TV aerial on the chimney stack but didn’t get permission from the Estate in advance, doing so only after the Factor noticed and called them out on the matter. These kinds of anecdotes are important to remind us that history isn’t just about exhibits and documents and notable events, but is predominately made up of the everyday, the millions upon millions of tiny moments of normality that accumulate into something we can only try to explore and then preserve as best we can.

And yet, even the fact that I, a second-year student from Oxford with no previous connection to the township, have come up here and gone through Eddie’s photographs and family paperwork, doing my best to acclimatise myself to the taste of the fifties, now seems normal to Eddie. Over a cup of tea in what used to be the MacCallum’s living room – now a meeting room colonised by interns for the summer, where I have been poring over 1950s catalogues and magazine adverts to try and find as close a match as possible to the furniture described by Eddie and noted on the receipt – Eddie told me he has become used to the museumification of his childhood home. Though the notion may seem strange to those of us who have not experienced it, the process of converting a house into history, of turning ‘Young Eddie’ into a primary source, has been going on for 50 years and, as is inevitable, has become part of history itself.

Images from top: The new Colt house at Auchindrain, February or March 1954; Eddie and Peggy MacCallum in the living room of The New House, late 1950s; and A page from the itemised receipt issued for the New House plenishings by Charles Rattray & Co Ltd, Glasgow, August 1954.